Bradford deLong has recently argued that neoliberalism provides a way for former colonies to close the gaps with their erstwhile colonial masters. But this argument ignores the fact that several economic policies of colonial times were explicitly laissez-faire in nature.

Bradford deLong has recently argued that neoliberalism provides a way for former colonies to close the gaps with their erstwhile colonial masters. But this argument ignores the fact that several economic policies of colonial times were explicitly laissez-faire in nature.

The recognition of the dangers of allowing finance a free hand in the economy has led to a rethink of the soundness of neoliberalism as an economic and policy doctrine, from no less an organisation such as the IMF. Dani Rodrik has attacked the theoretical foundations of neoliberalism itself, judging that its insistence on allowing for unhindered market activity is bad economics itself, for economic models that make a theoretical case for markets cannot be easily transplanted into the real world in the way that advocates of neoliberalism believe.

Yet this is not to say that the concept is dead and buried. As Harvey (2007) points out, neoliberalism is a political economic process that ostensibly seeks to organise society and economies around the principle of free market activity, while primarily attempting to shift the balance of power towards dominant economic classes that control capital. Seen in this light, neoliberalism is still a powerful force shaping political and economic changes in much of the world today.

Bradford deLong’s blog post, first published in 1998 and re-published now shows that the term “neoliberalism” still carries intellectual currency. His is a curious argument; neoliberalism provides the only suitable path for countries of the developing world to close the gap with their former colonial powers. Access to the latest goods and technology allows developing economies – with low levels of productivity – to boost productivity and output growth, and consequently incomes. The reason the State should stay away from the economic sphere in the developing world is because democratic institutions have not been established yet, and hence the political sphere is vulnerable to capture by elites.

This argument neglects the role of Western governments in fostering regime change and instituting the very same elites that would go on to suppress democratic rights. DeLong does highlight that the East Asian economies achieved high per capita income levels through the use of the Developmental State, but states that economic growth there came only at the cost of genuine political democracy and massacres by the military, completely glossing over the fact that economic progress and a “robust” social democracy in the developed world was built on the backs of large scale expropriation of surplus, political repression and torture and outright slaughter in the colonies.

The links between colonialism, capitalism and the subsequent development of Asian and African economies is well-known. Yet there is a deeper point to be noted; the dichotomy drawn by DeLong between colonialism and neoliberalism is false because colonial economic policy has always been neoliberal with respect to two important economic spheres, public finance and international trade.

The Laissez-Faire Colonial State

One of the hallmarks of neoliberal economic policy is the limited State intervention in markets, an adherence to reducing fiscal deficits, and a commitment to preserving laissez-faire. It could well be argued that the colonial state was not neutral with respect to the economy, and intervened with a heavy hand to preserve its rule. But in the economic sphere, it was thoroughly committed to the idea of laissez faire and balanced budgets.

As Morris D. Morris (1963) writes, “Government policy during the nineteenth century, despite its authoritarian characteristics, was in its economic aspects essentially laissez faire. The British raj saw itself in the passive role of night watchman, providing security, rational administration, and a modicum of social overhead on the basis of which economic progress was expected to occur”. The colonial state sought to ensure its budgets were balanced; it would only undertake investments if they generated adequate returns to cover their costs at market interest rates. India was a primarily agricultural economy, with a small industrial base, and hence State revenues were largely dependent on the monsoons.

This ensured that public spending was pro-cyclical, and that slowdowns were not compensated by injections of demand from the State. As Morris himself realises, this policy of the colonial government “…had adverse effects on the general responsiveness of indigenous entrepreneurship, reducing confidence and keeping the flow of capital into commerce and industry below what it otherwise might have been.”

These restrictions were not just seen in India, but was an essential feature of public finance in nearly all British colonies. As Stammer (1967) notes, colonial governments accumulated reserves during booms and failed to expand public spending during recessions, avoiding the use of deficit financing. The following quote by a British governor of an African colony – quoted in Stammer – perfectly outlines the neoliberal character of colonial economic policy:

“It is the duty of every African government, not to provide work for the workless, but so to govern that private enterprise is encouraged to do so; that trade is allowed to grow without hindrance; that business houses are given every facility and encouraged to start new productive works.” (Quoted in Stammer, pg 194).

It was only after the havoc wrought by the Great Depression that British economic policy towards its colonies changed, with the passing of the Colonial Development and Welfare Act in 1940, which ensured that colonies did not have to generate their own financial resources. Nonetheless, it is safe to argue that there was no essential change in the laissez-faire character of colonial powers when it came to the economic policy of the colonies.

Colonialism, Neoliberalism and the Shaping of Comparative Advantage

A focus on comparative advantage is associated with neoliberalism, suggesting that today’s developing economies should export agricultural and labour-intensive goods. There are two major problems with this assertion. Firstly, the successful export-oriented Asian economies of today consciously built up their technological capabilities and exported goods that had nothing to do with their “comparative” advantage. As Rodrik notes, much of the goods exported by China are of a far greater technological intensity than what would be appropriate to their relative supplies of labour and capital. The South Korean government provided subsidies and active State support to get firms to upgrade and export goods of a more capital and technologically intensive nature, as various authors – such as Vivek Chibber and Atul Kohli – attest.

The second problem is that the characterisation of today’s developing economy exports as being inherently labour-intensive and agricultural is ahistorical, for there is no real recognition of the impact of colonial policies on domestic manufacturing. Amiya Bagchi (1976) has written extensively on the “deindustrialisation” of Indian textile manufacturing and the impact of colonial policy over the 19th century.

To be sure, there exists a large debate about the exact causes of deindustrialisation in India. While Bagchi lays the blame squarely at colonial economic policy, Tirthankar Roy believes that technological and market changes were largely to blame. The industrial revolution led to an increase in productivity in Britain, and Indian industry simply couldn’t cope.

There is no doubt that Indian textile manufacturing in the 19th century was not as productive as British machine spinning. Yet it is important to understand that Indian textiles were forced to compete with British goods, which circulated freely within the Indian economy. In a sense, trade in India was truly “free”, for there was no impediment to the movement of British goods.

Colonial policy denied the Indian economy the very same tools the British economy adopted to spur technological change – the use of tariffs to protect the domestic economy and improve its technological capabilities. As Ha-Joon Chang (2002) has shown, Britain industrialised behind the wall of high tariffs during the 1800s, only lowering its tariffs in the middle of the 19th century, once it had established itself as a major manufacturing power. The dominant capitalist economy of today, the U.S., similarly had extremely high tariff barriers before it was ready to enter the free trade arena. Moreover, even though Britain did lower tariff barriers, manufacturers in Britain were still able to protect their markets from Indian goods. As Maddison writes:

“India could probably have copied Lancashire’s technology more quickly if she had been allowed to impose a protective tariff in the way that was done in the USA and France in the first few decades of the nineteenth century, but the British imposed a policy of free trade. British imports entered India duty free, and when a small tariff was required for revenue purposes Lancashire pressure led to the imposition of a corresponding excise duty on Indian products to prevent them gaining a competitive advantage.” (Maddison, 2006, pg 56).

Thus India’s “comparative” advantage in agricultural goods cannot be assumed to inherently characterise the economy, and must be seen in the context of a policy of free trade imposed upon it by its colonial power, Britain. The following quote by Tirthankar Roy demonstrates the essential compatibility between neoliberal policy prescriptions and the colonial experience with regards to free trade:

“…whereas British policy believed in exploitation of comparative advantage in trade, independent India turned firmly away from participation in the world economy, precisely at a time that the world economy experienced a boom. When economic reforms in the 1990s reintegrated India in the world economy, the major beneficiaries were manufactures that were intensive in semiskilled labor, in a late but welcome reversion to the colonial pattern of growth.” (Roy, 2002, pg 110. Emphasis added).

The adoption of neoliberal reforms in India after 1991 did lead to periods of extremely rapid growth, as compared to the period from 1947 to 1991 (though this cannot be taken as vindication of neoliberalism in general). But much of this growth has come from inflows of foreign finance (Nagaraj, 2013), which curtails the policy space available to the government, which must now cater to the wishes of finance capital. While colonialism benefited foreign capital, neoliberalism shifts the balance of power to big domestic capital and international finance capital. It is a cruel irony therefore, to hail neoliberalism as an antidote to colonialism, as neoliberal economic policy was one of the highlights of colonial policy, bringing in its wake severe hardships for much of the world’s population.

References

Bagchi, A. K., 1976. De-Industrialization in India in the Nineteenth Century: Some Theoretical Implications. The Journal of Development Studies, 12(2), pp. 135-164.

Chang, H.-J., 2002. Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective. London: Anthem Press.

Harvey, D., 2007. Neoliberalism as Creative Destruction. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volume 610, pp. 22-43.

Maddison, A., 2006. Class Structure and Economic Growth: India and Pakistan Since the Mughals. s.l.:Routledge.

Morris, M. D., 1963. Towards a Re-interpretation of Nineteenth Century Indian Economic History. The Journal of Economic History, 23(4), pp. 606-618.

Nagaraj, R., 2013. India’s Dream Run, 2003-08: Understanding the Boom and its Aftermath. Economic and Political Weekly, 48(20), pp. 39-51.

Roy, T., 2002. Economic History and Modern India: Redefining the Link. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(3), pp. 109-130.

Stammer, D., 1967. British Colonial Public Finance. Social and Economic Studies, 16(2), pp. 191-205.

Rahul Menon is Assistant Professor in Economics at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Hyderabad, India.

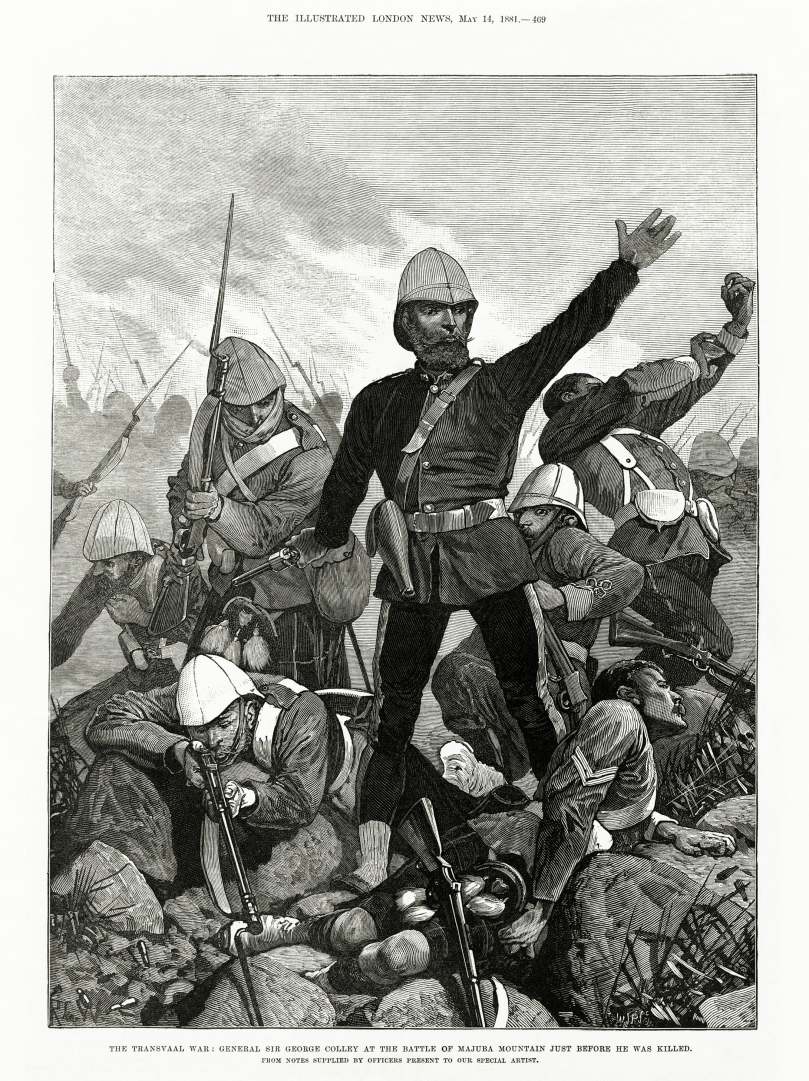

Photo credit: Melton Prior

“Recently”? It was 1999, IIRC…

LikeLike

Your piece does not seem to engage my argument for why I call neoliberalism “a counsel of despair”. My argument is, in a nutshell:

>By the end of the 1970s, however, it was clear to all except blindered ideologues that something had gone very wrong with social democracy at the periphery. (And that even more had gone wrong with really-existing socialism at the periphery.) Stable political democracy proved far more to be the exception than the rule. Authoritarian rule by traditional elites, dictatorship by impatient army officers, and charismatic populist politicians ruling by virtue of carefully-prepared and carefully-staged plebiscites were much more common than were stable parliamentary or separation-of-powers democracies….

>As Marx wrote, the executive branchy of the modern state is nothing but a committee for managing the affairs of the ruling class—meaning, among other things, that a democratically-elected legislative branch turns the state into something better. But the prospects for stable political democracy in the periphery are slim. And thus the government becomes the tool of the ruling class—a ruling class that may be made up of army officers, or landlords, or urban elites, or those who profit as middlemen from the traditional channels of trade and exchange—who are not terribly interested in the success of social democracy or in rapid broad-based economic growth.

>Hence the policy advice of neoliberalism as a counsel of despair: get the state’s nose out of the economy as much as possible. When the state is neither an instrument of positive redistribution nor an instrument of growth-boosting investment, its interventions in the economy are likely to go strongly awry. And to the extent that a reduction in the economic role of an elite-controlled state can be required as a price for rapid incorporation of an area into the global economy, such a reduction should be required.

LikeLike

Hi Dr DeLong. Sorry for the late reply. I did not engage with the argument of neoliberalism as “counsel of despair” because I was interested in another aspect, that of the similarities between neoliberalism and colonial economic policy and hence the problems with thinking of neoliberalism as a positive policy solution for former colonies.

However, I did allude to this argument, where I mentioned how America often colluded to bring about the very same elites in power in several countries that would go on to render democracy unworkable, thereby rendering statements like “the prospects for stable political democracy in the political periphery are slim” extremely problematic. Moreover, I don’t think I can agree with the idea that neoliberalism represents a suitable policy for economies with heavy-handed governments, because neoliberalism has often made use of and supported those very same governments that go on to repress human rights and political freedoms. If neoliberals were committed to the idea that authoritarian governments are detrimental for an economy, Margaret Thatcher and Milton Friedman would never have engaged with Augusto Pinochet, but they did.

LikeLike

Very stimulating article, opening new directions to explain the structural economic and social crisis in some postcolonised countries, like Algeria.

LikeLike

Nice article Rahul, but I think that there are certain specificities of neoliberalism historically. What I mean is that the existence of pro-free market policies and a laissez-faire attitude towards trade internally don’t make something neoliberal necessarily, especially in the historical context of colonialism.

LikeLike

Hi Madhav. I don’t mean to imply that adopting a balanced budget makes a regime neoliberal. I don’t mean to imply that colonialism is the same as neoliberalism. I only meant to point out certain similarities between economic policy in a colonial regime and under neoliberalism. Perhaps I have been a little looser with definitions than I would like, but my point is simply to point out the similarities in the conduct of economic policy under the two regimes. There will be differences; colonial policy would require a balanced budget, while neoliberalism would say that the deficit must be capped at 3% in India. But the differences, I would argue, would only be those of degree, and not of kind. I was interested here in the similarities, while in now way denying that historical specificities are important in defining the overall character of colonialism vis-a-vis neoliberalism.

LikeLike