The spread of the coronavirus epidemic around the world in the past few weeks has exposed not only differences in the lack of preparedness of various public health systems, but also differences in reactions to the crisis. Some governments imposed an early lockdown in their attempt to ‘flatten the curve’ while others have taken a more gradual approach, proceeding from travel restrictions through limits on non-essential businesses to shelter-in-place regimes.

As the epicenter of the pandemic shifts from Asia to Europe and the U.S, however, some reactions stand out among the rest in their utter disregard for human life. Federal and state officials in the U.S. have first downplayed the threat two months before it arrived in the country, as well as refused offers for help from the World Health Organization. Now, as the curve in the U.S. is about to get steeper (see the surgeon general’s warning), top levels of government are considering scaling back the moderate measures that have been taken so far, with a view to return to normal activity within a few weeks. While blaming China for not controlling the virus early enough, some officials are contemplating consciously allowing their own citizens to experience a much worse spread of infection and death than China has seen.

One clear example of this misguided and dangerous ideology can be seen in the pressure put on the U.S. government by corporate lobbyists not to activate the Defense Production Act – which enables the executive branch to order corporations to manufacture the direly-needed medical supplies for testing and treating the virus. Large swaths of the political elite, instead, are relying on the private sector’s voluntary offers to produce such goods. Worse, these same politicians are aching to get the economy back to normal, so as to boost the stock market and their own ratings at the same time. The lieutenant-governor of Texas even went as far as suggesting that older citizens – the group most prone to dying from the virus – would gladly ‘sacrifice’ themselves in the interest of getting the economy moving again.

How can this idolizing of the economy over the polity – and citizens’ very survival – be possible in a democracy? Those in power are clearly acting in their own self-interest rather than in that of the public. Most people are probably scratching their heads for an explanation of how this could be happening in a country previously considered the beacon of freedom. A straightforward explanation is that the U.S. has not been a real democracy for a while, if by that term one means enacting policies in the interest of the voting majority. While it had never topped the EIU Democracy Index, the U.S. has dropped from ‘full democracy’ to ‘flawed democracy’ in 2018.

But this decline has been in the works since 1980. From that time, economic ‘freedoms’ have increased in the U.S., as corporations, consumers, investors and wealthy individuals have benefitted more than ever from improvements in technology, healthcare, education and other aspects of living in a rich society. The majority of the population, however, has been doing worse, as evident by stagnating or declining real wages, increasing inequalities in various dimensions, and even a drop in life expectancy for some population groups.

In short, the U.S. is only a nominal democracy, in that anyone of voting age can select candidates for local, state and national office and also run for such office. However, the two-party system, coupled with the unparalleled impact of money in political campaigns (made worse by the Citizens United decision of the supreme court) have deflated the power of electoral democracy, since both major parties in the U.S. accept enormous donations from corporations, and are also lobbied much more by firms than by non-profit organisations or individuals (as the latter two groups do not have nearly the same financial resources as private firms). The expansion of economic freedom then – at least of this sort – has come at the expense of political freedom and representation of the public interest, which is now merely a pretense.

While the US had both political and economic freedoms – at least immediately after WWII – it has since sacrificed its citizens’ political freedoms for more corporate freedom. The US case shows that what has long been known as Laissez-Faire – leaving the economy to its own devices – works to diminish political freedoms and make democracy a sham.

To return to the virus, the U.S. may end up in a much worse place than other, poorer countries. Its extreme neoliberal policies of the past four decades have weakened its public health system, while also brainwashing millions of voters to see the government as the enemy. Thus, one of the richest countries on earth faces shortages of everything from masks, testing equipment, ventilators and even medical staff. Laissez-Faire, in the extreme, means Laissez-Mourir (let die): more people are left to die as public services have been savaged by years of austerity.

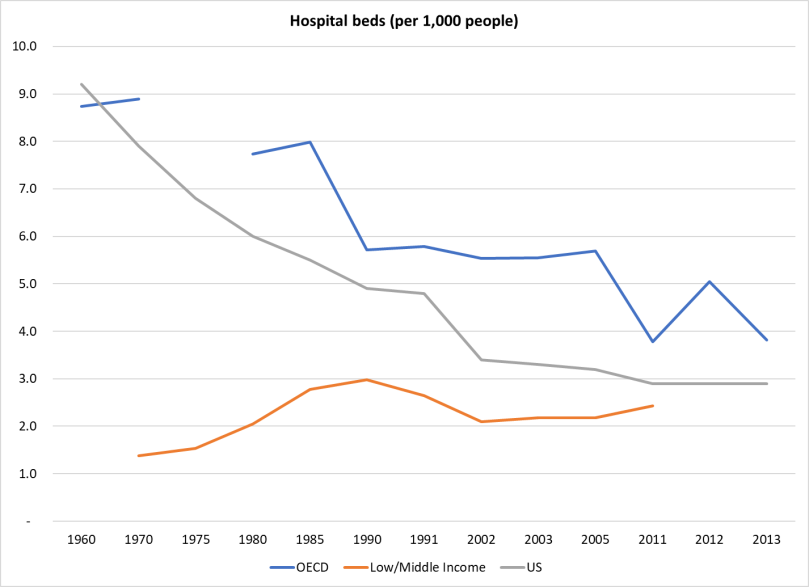

As the chart below shows (using World Bank data), the U.S. was leading the world in 1960 with 9.2 beds per 1000 people (compared to 8.7 in the OECD, the group of industrialized countries). By the second decade of the 21st century, this ratio dropped to 3 (a decrease of two-thirds) in the U.S. while the OECD was averaging about 4. Meanwhile, poor and emerging countries have increased their hospital capacity from 1.4 in 1970 to 2.4 in 2011.

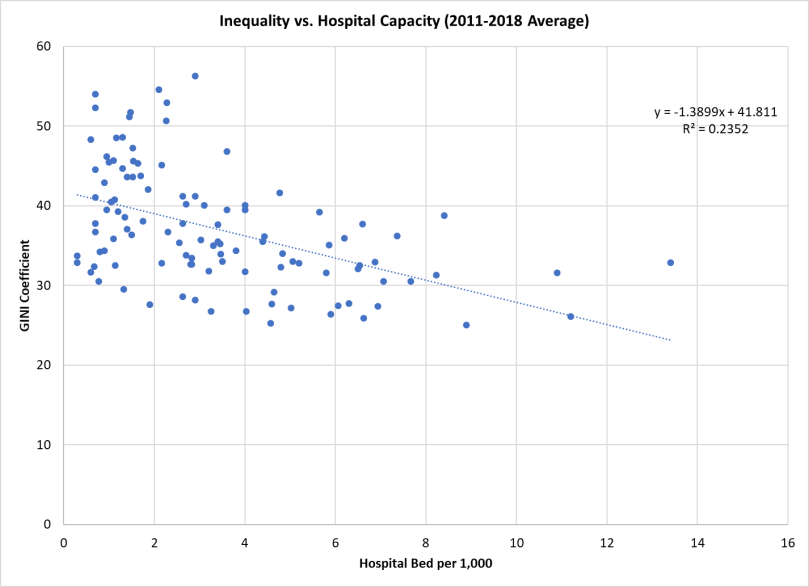

As data on the spread of the virus is still being collected, it is instructive to compare hospital capacity across countries. The chart below shows that more unequal countries have, ceteris paribus, less beds per 1,000 people. But the link is neither perfect nor deterministic. While the U.S and China had similar average levels of inequality of the period 2011-2018 (41.2 and 40.1, respectively), China has 4 beds per 1,000 while the U.S. has 2.9. Serbia and Russia are only slightly more equal (with Gini coefficients of around 39 for both), but have 5.7 and 8.4 beds per 1,000 people, respectively. Japan and Korea, which were earlier the epicenter of the pandemic, coped very effectively with the crisis, partly since they have 13.4 and 10.9 beds per 1,000 people, respectively. In other words, these two countries have 3-4 times more hospital capacity than the U.S., despite their per capita income being about third lower (even using PPPs).

Hospital beds are not the only factor in a country’s ability to respond to a pandemic, but they do play a role, especially when more people start getting infected. As of Friday, 27 March, the infection rate in the US was far worse than many other countries which were affected earlier:

| Country | Cases per 1 million people | Hospital Beds per 1,000 – latest year | GNI per capita ($PPP) – 2018 |

| U.S. | 250 | 2.9 | 63,690 |

| China | 57 | 4.2 | 18,170 |

| Hong Kong | 60 | 4.9 | 67,810 |

| Japan | 11 | 13.4 | 44,380 |

| South Korea | 180 | 11.5 | 40,090 |

There is another sense in which Laissez-Faire is literally deadly. Leaving the fate of the environment and the planet in the hands of the market has produced a threshold-level catastrophe, and even now, with only a few years left – if any – to take action on climate change, the U.S. is in denial about its very existence. And it’s not just future generations who will suffer. Recent research has tied the spread of deadly viruses to humans’ ever increasing encroachment onto previously untouched natural environments. When species in those areas go extinct, disease vectors such as COVID-19 find new homes in the bodies of humans.

This double-danger of Laissez-Faire – hurting people, destroying the environment and thus hurting even more people in the name of economic growth – is not new to many developing countries, where decades of Washington Consensus policies have ravaged social safety nets, commodified the environment, and emptied democracy of its content as elected government were powerless against (or alternatively, colluding with) multinational corporations. Ironically, global corporations appeared first as instruments of colonization (e.g. the British and Dutch East India companies), but during the industrial revolution came home to roost, ‘colonizing’ working classes in the rich countries’.

Maybe now, as the dangers of infectious disease, social breakdown, and even economic meltdown occur in rich countries, people there may finally take notice. Austerity – the latest form of Laissez-Faire in the North – has hollowed countries’ ability to not only support the vulnerable in normal times, but even to save their lives during a pandemic. And while it is true that the viral infections do not discriminate by income, the poorest are most vulnerable and least equipped to cope with them, also in rich countries.

The virus may be blind to political beliefs, but not vice versa. It may be a coincidence that so-called ‘red-states’ in the U.S. have reacted more slowly and with less concern than ‘blue states’ to the virus, and some are already contemplating going back to normal, or that republican senators seem to be more affected by it than their democratic colleagues.

However, the poor and middle-classes of both parties will likely suffer far more than their politicians. The same happens during wars, where the bulk of ordinary soldiers are drawn not from the top but from the bottom and middle of the social hierarchy. But World-War II showed not only the horrors of war, but also the enormous potential of collective action, including the boost it gave to the U.S. economy, the disappearance of unemployment, the demonstration of women’s equal ability to work, as well as the virtue of balancing political and economic freedoms, which is the only stable path to real democracy.

The recent virus is a tragedy given the lives already lost and those who will die next, the economic hardship and rising unemployment, and the complete disruption of a way of life once taken for granted. But it is also an opportunity to remember that pushing private, economic freedoms to their limit is not without a cost. They come at the extent of political freedoms, public goods such as health and safety, and ironically – even at the cost of long-run economic well-being itself. Just as the stock-market crash of 1929 helped elect FDR and rebalance economic and political freedoms – even before the outbreak of WWII – we can only hope that the economic slowdown currently affecting the U.S. and other countries will shake voters of all political stripes out of their fairy-tale belief in the market as a guarantor of any freedoms – economic or political – in the long run.

A pandemic, like fascism, cannot be priced in by markets. It is not an externality to be internalized by a tax. It cannot be traded between those with different ‘endowments’ of the disease. It takes a society to fight a war, and as several countries have already shown during this crisis, Maggie Thatcher was wrong: there is such as a thing as society. While we need to be cautious not to to curtail political freedoms, we cannot sacrifice ourselves to the short-term ‘economic freedoms’ of a minority. If we do, we are all dead, even before the long-run.

By Dr. Jacob Assa, The New School for Social Research. He Tweets at @jacob_assa.

Photo: Emergency hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas in 1918.

[…] via Laissez-Faire, Laissez Mourir — Developing Economics […]

LikeLike

[…] many public institutions that would otherwise have helped to mitigate the current crisis, including health care. The state’s “organized abandonment” was accompanied by a retrenching of the state’s […]

LikeLike

[…] Assa, “Laissez-Faire, Laissez Mourir”, https://developingeconomics.org (31 March […]

LikeLike