By Susan Newman and Sara Stevano

Johnson’s announcement on 16 June that Department for International Development (DfID) would be merged into the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) has been met with criticism and condemnation from aid charities, NGOs and humanitarian organisations. By institutionally tying aid to UK foreign policy objectives, the merger would shift humanitarian aid away from the immediate needs for relief and longer-term development.

This latest move to merge the departments should be seen as the latest, and a very significant, step in the restructuring and redefinition of British Official Development Assistance (ODA) to serve the interests of British capital investment abroad, that has been taking place over the last decade. These developments need to be considered within a wider shift in development policy that has been shaped by the demand for new assets by investors in the global North in the context of a global savings glut that has grown out of economic slowdown.

The last 30 years have seen dramatic transformations in the role of British aid in international development. DfID was formed in 1997, when it was separated from the FCO. Such disincorporation came with a partial redefinition of development away from the protection of capital’s interests enmeshed with the UK’s former colonial ties, and an embracing of the security agenda and the universalisation of development as moral imperatives. The UK played a significant role in shaping the global development agenda, with Clare Short, Secretary of DfID under New Labour, taking the lead in the promotion of the International Development Goals (IDGs), which paved the way to the development of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

Amidst the economic and political turbulence of the global financial crisis and its austerity-shaped aftermath, there has been a recent shift in the strategic focus of the UK aid strategy. Growing importance is now again attached to promotion of the UK’s national interest. A key mechanism for achieving this, as set out in the 2015 aid strategy, has been to direct the aid budget away from DfID to other government departments and cross-government initiatives. Between 2014 and 2016, there was a 12 percentage point drop in the proportion of the ODA budget received by DfID, so that by 2016 more than a quarter of the aid budget (£3.5 billion) was being spent outside DfID, up from 14% two years earlier.

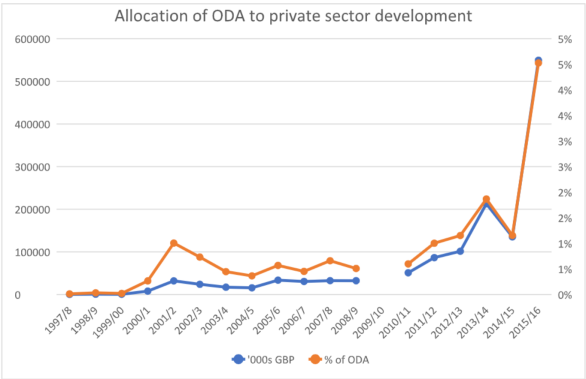

There is a long history of private sector involvement in British overseas development but there are qualitative changes linked to the restructuring of the British ODA apparatus. Striking changes can be observed in the allocation of ODA to private sector development, with dramatic increases from 2013/2014 onwards.

Source: Created by authors using data from DFID Annual Report 1997-2015/2016

Source: Created by authors using data from DFID Annual Report 1997-2015/2016

Commercial interests and private sectors involvement have been part and parcel of British ODA since the outset with concessional lending tied to procurement of goods from the UK and the provision of export credit at favourable terms by private banks subsidised and guaranteed by government to win business from developing countries. For the majority of its history, ODA has been the remit of the Foreign Office. The Colonial Development Corporation (now named the Commonwealth Development Corporation, CDC) was formed in 1948 with the mission to ‘do good without losing money’ and ‘augmenting the productive capacity of the colonies to provide food and raw materials to meet the pressing needs of post-war Britain’. CDC was partially privatised in 1999 only to be brought back into government ownership, via its purchases of all private equity in CDC in 2012, to become the UK’s main development financial institution. Mawdsley refers to the CDC as the ‘centrepiece of existing mechanisms’ to encourage partnerships with business. For example, the CDC has taken an interest in the so-called gig economy in Africa owing to its potential to generate returns for investors with limited investment sufficient to offer some ‘perks’ to workers, such as training and links multinational companies, that cannot be obtained via employment in the informal economy.

Johnson described the DfID budget as a ‘great cashpoint in a sky’. DfID’s budget had indeed bucked the trend during a decade of austerity. Not only were no cuts made to the department, an injection of finance was made to bring CDC back into full government ownership under the Commonwealth Development Act of 2017. Over the last 10 years, DfID has undergone considerable internal restructuring in relation to its strategy to support private investment in the Global South through vehicles such as public–private partnerships and development impact bonds. An expansion in the expenditure of its Corporate Performance Group from 0.05% of the DfID budget in 2008/9 to 3.2% by 2015/16, and its commitment to Payment by Results as part of aid strategy in 2015, reflect a shifting role for DfID towards the monitoring and evaluation of private businesses on behalf of UK investors.

The merger of DfID into the FCO is thus the latest in an ongoing reorientation of British ODA. It is nonetheless significant because it marks a more defined break away from aid as humanitarianism. The re-incorporation of DfID into the FCO reduces the possibility to align British aid with the interests and development plans of recipient countries, thus giving rise to a ‘new-model colonial policy’, as recently argued by Oqubay. It places ODA firmly within a narrow nationalist agenda with deep resonances with empire that stands opposed to the raging Black Lives Matter movement and the calls for reckoning with the imperialist history of the UK. This is all the more significant in the current historical moment, when the anti-racist movements have been reignited in the UK as the Covid-19 pandemic is making visible how institutionalised racism can make the difference between life and death, with BAME people disproportionately affected by coronavirus owing to their economic deprivation, social marginalisation and over-representation among low-paid ‘essential’ workers.

This merger drastically completes a longer-term process of restructuring of British ODA by annihilating the possibility for aid to be used primarily for humanitarian relief based on immediate needs or to deal with longer term issues of poverty reduction and economic transformation through industrial policy. As unwelcome as this merger may have been at any time, its announcement amidst a pandemic that is ripping through the Global South, the global economy set for a protracted downturn, the global upheaval against racism and the colonial past in opposition to right-wing nationalist populism make it particularly damaging and politically charged.

Professor Susan Newman is Head of Discipline for Economics at The Open University.

Dr Sara Stevano is Lecturer in Economics in the School of Oriental and African Studies.

Image: Michael Haig/Department for International Development

Hello,

I work for CDC. This blog contains two separate ideas: 1) using ODA to further the interests of British capital and 2) the recent decision by DFID to put more money into CDC. In case not obvious to your readers, it might be worth pointing out that CDC has no mandate to support British businesses* and if you browse our investments, you will see most of our investments in businesses that have no connections to the UK. We make investments that we think are good for development, and we don’t care about the nationality of the owners or other investors.

You conclude that “This merger … [annihilates] the possibility for aid … to deal with longer term issues of poverty reduction and economic transformation through industrial policy”. I would say that dealing with the long term issue of poverty reduction and economic transformation by investing in strategically important sectors (not too dissimilar to industrial policy) is exactly what CDC exists to do. Whilst I would share your concerns if our development-oriented mission were to be diluted, as of now our mandate remains unchanged.

* this is the job we have been given: https://assets.cdcgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/25150902/Strategic-Framework-2017-2021.pdf

LikeLike

We very much appreciate the CDC colleague’s response to our blog post and for the opportunity it provides for us to unpack and clarify some of the issues that have been raised.

The cash injection by the government to bring the CDC fully into DFID ownership has been central in the reorientation of British ODA towards the private sector in the Global South in the interests of private capital, primarily but not limited to British capital.

The CDC has no mandate to support British business, but it does have a mandate to secure financial returns on investments. The “development-oriented mission” of the CDC is narrowly focused upon the private sector and investment in “strategically important sectors”, such as infrastructure, for which investors can receive a return. Whilst these might be aspects of industrial policy, they do not constitute industrial policy. Industrial development appears only once in CDC Strategic Framework 2017-2020 that our colleague has shared to better represent the work of CDC, and only in relation to infrastructure investments. Indeed the Independent Commission for Aid Impact’s (ICAI) performance review of CDC https://icai.independent.gov.uk/report/cdc/ highlights that CDC investments are concentrated in financial services and infrastructure, while they have been declining in manufacturing between 2011 and 2017 (time period covered by the review).

It should be noted that PPP infrastructure projects have proven to be extremely costly for recipient countries in many cases, as evidenced by research (for example, see Eurodad report https://eurodad.org/whatliesbeneath). A critical area is health care, where the UK health ODA channelled through the CDC is increasing, thus in favour of for-profit health care, which raises concerns over DfID’s commitment towards universal health care (see BOND’s report https://www.bond.org.uk/resources/the-uks-global-contribution-to-the-sustainable-development-goals). The development strategy implicit in CDC investment decisions appear to rely on market centred view of development that sees all investment as good investment as far as recipient countries are concerned. It is sometimes difficult to see what developmental impact CDC investment has delivered. Take for example Chai Bora, a tea processing firm based in Tanzania. According to the CDC website, they invested in Chai Bora through a private equity fund, Catalyst Fund I, which is managed by Catalyst Principal Partners. Catalyst Principle Partners is private equity fund manager working from Nairobi and registered in the tax haven of Mauritius. But this is not the first time that CDC has had a stake in Chai Bora. Chai Bora Ltd. was established in 1994 as a subsidiary of Tanzania Tea Packers Limited (TATEPA) in which CDC had a 53% stake. The CDC contributed to the expansion of the business in these early years. In 2006 CDC transferred its 53% holding in TATEPA to Actis Africa Agribusiness Fund, a London-based private equity firm through which the CDC continues to channel investments. In 2008, Chai Bora was purchased by the Kenyan private equity firm TransCentury, from whom it was acquired by the Catalyst Fund I, financed by CDC. The buying and selling of equity in Chai Bora has clearly been a lucrative endeavour but what has been the developmental impact of this investment in terms of tax income and reinvestment of profits in Tanzania? These are not key metrics with which the CDC assess the developmental impact of investment. The colleague might argue that this mode of investment allows for the recycling of funds to greater effect and provide the potential for expanded investment but there are much more effective and direct ways to invest for more immediate and sustainable economic development than to rely on trickledown from private investors through equity funds that traverse tax havens.

Even on its own terms, the developmental impact of CDC investment is questionable. The ICAI report on CDC’s investment in low-income and fragile states published in March 2019 awarded CDC an amber-red overall score. The report concluded that “CDC has made progress in redirecting investments to low-income and fragile states but has been slow in building in-country capacity to support a more developmental approach. CDC has not done enough to ensure or monitor development results, or to progress plans to improve evaluation and apply learning”.

CDC is the development finance institution for British ODA and its mandate, strategy and operations reflect the reorientation of British ODA towards the primary interests of private capital and not development. At the UK-Africa Investment Summit held in January 2020 in London, the chief executive of the CDC commented: ‘Clearly, post-Brexit, we have more flexibility to form trade relationships. Africa has to be a significant priority for UK business and UK investment.’, as reported by the Financial Times https://www.ft.com/content/e9d5b771-53f3-4066-a4c8-133df96502f4.

LikeLike

Phew, there’s too much for me to try to respond to there. I want to respond to just one element,

As you know, many of the countries in which we invest have national investment strategies. You also seem to approve of activist industrial strategies (as do I). These things involve attracting investment to build productive, profitable businesses. Are these strategies serving the “primary interests of private capital and not development”? No, they are about investment for development. As we all know, long run poverty reduction requires more productive economies. Whilst there are some circumstances (large positive externalities etc.) where one might want to operate enterprises at a loss (by subsidising it) as a rule enterprises whose revenues cover their costs (labour, capital, inputs) create value, those that do not destroy it. An industrial policy that created lots of loss-making enterprises would probably be doing more harm than good. The greatest movement of people out of extreme poverty the world has ever seen – China – was in large part driven by a protracted investment boom. So the countries where CDC operates want to see more investment, they want to see the creation of profitable enterprises, and we all understand the importance of that for long-run development and poverty reduction.

And yet in your eyes when CDC does these things we are serving the interests of private capital, you are highly skeptical that the creation of successful private enterprises is good for development, and you see a pernicious implicit market centred view development. Do you think the same of African national development banks? Of course we “narrowly focussed on the private sector” – that’s our role – we are part of the wider UK aid effort that has other parts that are focussed on other things. You wouldn’t criticise the private sector window of the African Development Bank for being narrowly focussed on the private sector. That’s what it says on the tin. The UK provides finance to sovereigns via the MDBs and RDBs, It doesn’t need CDC for that. Of course we have mandate to secure a financial return on investment – we are in the business of trying to create profitable enterprises. If you put $10m of equity into a business if it does well over time that equity should be worth more than $10m. A successful business can repay it loans. As a rule, we don’t have a positive impact on development by creating businesses that go bust. If the UK creates a national investment bank (https://labour.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/National-Investment-Bank-Plans-Report.pdf) it too will have a mandate to make financial returns. That’s what development banks do. That is what CDC does.

Here’s a something on Chai Bora, it looks to me like the sort of business Tanzania could use more of

https://www.cdcgroup.com/en/emerging-markets-investment/creating-jobs-tanzania/

I would be more than happy to continue this conversation via other means another time, but I think I need to get back to work so I won’t make any more comments on this blog.

LikeLike

[…] shift humanitarian aid away from the immediate needs for relief and longer-term development’.35 The Oxford Research Group have also raised this point, pointed to the fact that DFID usually […]

LikeLike