Women are the reason why men have changed because women are hard on men. […] The expectations they come with into a relationship, and generally how they have been brought up, or the life they live, that is what gives some men stress. […] When someone is living with a woman in the house, you find that issues are many because money is little.

Wellington Ochieng, 36-year old labor migrant from western Kenya

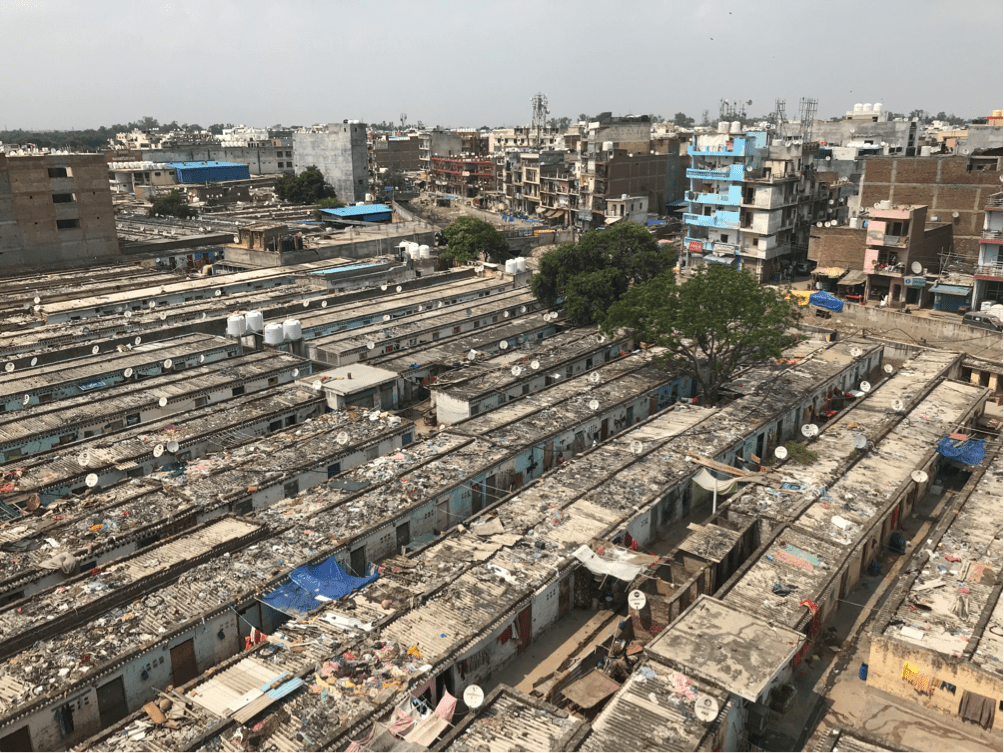

During almost three years of ethnographic fieldwork among male migrants in Pipeline, an over-populated high-rise estate in Nairobi’s chronically marginalized east, I heard complaints like Wellington’s almost daily. Migrant men, in my case predominantly Luo from western Kenya who came to Nairobi with high expectations of a better future, bemoaned a life full of pressure caused by the romantic, sexual, and economic expectations of their girlfriends, wives, and rural kin. The blame often lay on ‘city girls’ who were portrayed as materialistic ‘slay queens’who ‘finish’ men by leaving them bankrupt only to suck away the next sponsor’s wealth after grabbing him with their ‘Beelzebub nails’ as Wellington called the colorful nails sported by many Nairobi women. Soon, so a fear expressed repeatedly by my interlocutors, most men would no longer be needed at all and Kenya’s economy would be ruled by economically powerful women who raise chaotic boys brought up without an authoritative father figure. Such fears of male expendability also manifested in imaginations about a future in which more and more men and women would live in homosexual relationships or ‘contract marriages’ that replace trust and love with contractual agreements. When my flat mate Samuel, a student of economics divorced from the mother of his baby son, returned to our apartment after passing the neighbor’s house where a group of women celebrated a birthday, for instance, he just shook his head and sighed: ‘We live like animals in the jungle. Women and men separately. We only meet for mating and making babies. Maybe that’s where we’re heading to.’ Overwhelmed by their wives’ and girlfriends’ expectations, many migrant men who spoke to me in Pipeline decided to spend as little time as possible in their marital houses. Instead, they evaded pressure by lifting weights in gyms, stockpiling digital loans and informal credits, placing bets in gambling shops, gulping down a cold beer in a Wines & Spirits, playing the videogame FIFA, or catcalling ‘brown-skinned’ Kamba women on the roads. Some men who could no longer cope took even more drastic measures involving murder and suicide. One man, for instance, cut the throat of his girlfriend only to try to kill himself, while another tried to poison himself, later quoting the wife’s actions and character as the cause. Anything appeared better than spending time with the ‘daughters of Jezebel’ who were waiting for them in the cramped houses of Pipeline, sometimes demanding migrant men to engage in romantic and sexual practices they were unfamiliar with as expounded upon by Wellington:

When you come to Nairobi, our girls want that you hold her hand when you are going to buy chips, you hug her when you are going to the house, I hear there is something called cuddling, she wants that you cuddle, at what time will you cuddle and tomorrow you want to go to work early? […] you don’t go to meet your friends so that you show her you love her, you just sleep on the sofa and caress her hair, to me, this is nonsense because that is not romantic love, I think that romantic love, so long as I provide the things I provide, and we sire children, I think that’s enough romance. […] Another girl told me to lick her, and I asked her ‘Why do you want me to lick you?’ She said that she wanted me to lick her private parts. Are those places licked? […] Those things are things that people see on TV, let us leave them to the people on TV.

Figure 1: Pipeline

Read More »