It is official: we are getting ready for another round of industrial action in the UK higher education sector. For those who may be wondering what the current UCU national strike 2021-22 is all about, a short recap may help. Higher education UCU members are striking because of planned pensions cuts that risk pushing academic staff into ‘retirement poverty’; to fight against ever-growing labour casualisation in universities; and because of the growing inequalities of gender, race and class the UK higher education sector has nurtured in the last five decades. Colleagues at Goldsmith – to whom we shall extend all our support – are also fighting against planned mass staff redundancies.

We – higher education workers and students – were on this picket before, so many times, fighting other policies deepening the process of commodification of education. We were on this picket fighting cuts in real wages – which education workers are still experiencing. We were on this picket to fight against the trebling of university fees for our BA students. At SOAS, where I work, we were on this picket to fight against cuts to our library, against Prevent, against the deportation of SOAS cleaners on campus ground – an event which remains the darkest chapter of SOAS industrial relations and for which the university has not yet apologised in recognition of the harm caused to the SOAS 9 and to all our community. We hope the school will acknowledge the need to do so, so that we can move forward, together.

We were at other demonstrations and on other picket lines, protesting against austerity, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, against climate change, against racism and in support of Black Lives Matter, against gender violence. The picket really is a sort of archive, which can be consulted backward to reconstruct a history of attacks to our rights – at work, at home, or both.

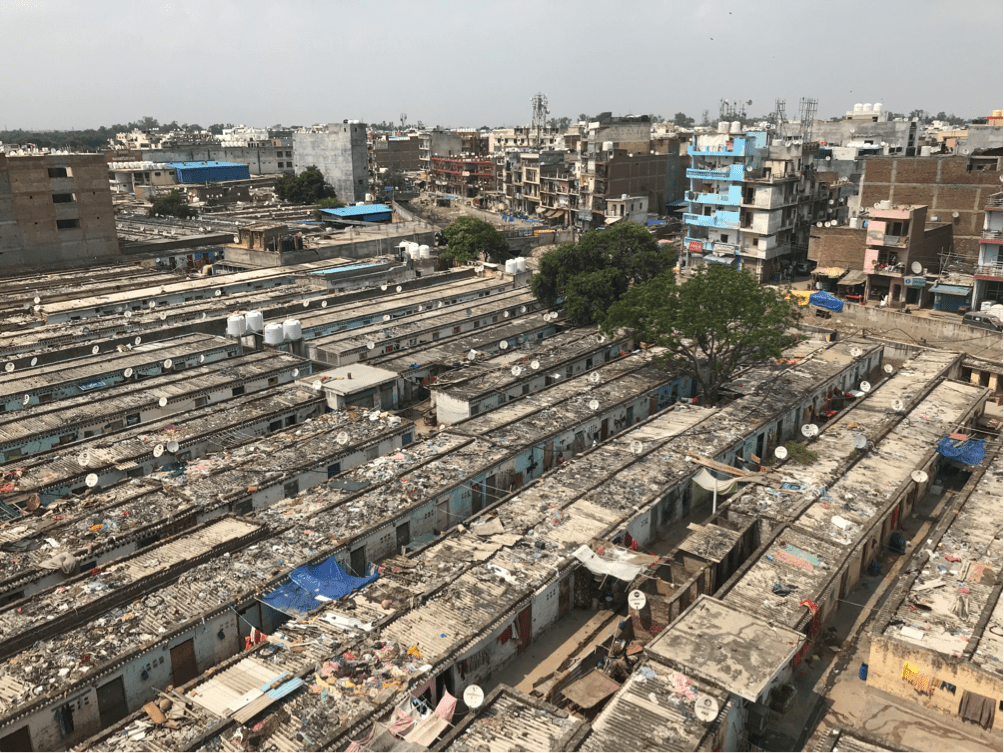

And if we consult this archive, we can clearly see a pattern emerging in the last decades, a pattern which in fact connects neoliberal Britain with many other places in the world economy, which have also experienced processes of neoliberalisation. All the pickets and demonstrations, become a sort of tracing route; we can reconnect the dots spread across a broader canvas. These dots design a specific pattern; that of a systematic attack to life and life-making sectors, realms and spaces.

Neoliberal capitalism, starting from the 1980s, has promoted a process of systematic de-concentration of resources in public sectors, and particularly in so-called ‘socially reproductive sectors’, that is those that regenerate us as people and as workers. This attack has been massively felt in the home, which has become a major battleground for processes of marketization of care and social reproduction. The withdrawal of the state from welfare provisions, the rise and rise of co-production in services (i.e. the incorporation of citizens’ unpaid labour in public service delivery; a practice further cheapening welfare) – and processes of partial or full privatisation of service delivery in healthcare and education have generated massive reproductive gaps. These gaps have been filled through outsourcing of life-making to others. Homes have become net users of market-based domestic and care services. The in-sourcing of nannies, au-pairs, and elders carers, from a vast number of countries in the Global south and transition economies have remade the home as a site of production and employment generation, at extremely low costs.

Read More »