The eclipse of neoliberalism in 2000s coincided with the so-called commodity ‘super cycle’ that lasted between 2002 and 2012. In search of a new model, resource-rich states began to articulate resource nationalism as a development strategy. While ownership and control of minerals and hydrocarbons are intricately tied to claims of state sovereignty and exercise of political authority in development policy, resource nationalism can also be understood in terms of a power struggle between host states and global hegemons in their quest to secure resources for their own industrial needs. Hence, contemporary natural resource governance is reflective of the wider ideological return of the state despite two decades of reforms promoting market liberalization and privatization. Resource nationalism is a vital expression of the renewal of state agency amidst high external constraints imposed upon resource-rich countries.

The eclipse of neoliberalism in 2000s coincided with the so-called commodity ‘super cycle’ that lasted between 2002 and 2012. In search of a new model, resource-rich states began to articulate resource nationalism as a development strategy. While ownership and control of minerals and hydrocarbons are intricately tied to claims of state sovereignty and exercise of political authority in development policy, resource nationalism can also be understood in terms of a power struggle between host states and global hegemons in their quest to secure resources for their own industrial needs. Hence, contemporary natural resource governance is reflective of the wider ideological return of the state despite two decades of reforms promoting market liberalization and privatization. Resource nationalism is a vital expression of the renewal of state agency amidst high external constraints imposed upon resource-rich countries.

Resource Nationalism as a State-led Development Strategy

It is not a coincidence that resource nationalism returned in mainstream political debates at the same time as emerging powers designed new industrial policies aimed at recalibrating state-market relations in favour of the former. With extraordinary high prices and rising demands for natural resources from China, domestic political configurations in resource economies appear to move towards reforms aimed at (1) capturing and maximising windfall profits amidst a boom, (2) extending the role of state in commodity production through a renewed role for state-owned enterprises, and (3) renegotiating the terms of contracts with multinational mining capital.

These policies are emblematic of a wider trend: the growing importance of state stewardship for industrial transformation in an era of cross-border production networks governed by global lead firms. Despite the rhetoric on economic globalization, the role of the state remains prevalent as observed in the number of state-owned enterprises, the significant expenditure on industrial policy, and the array of government-business partnerships in East Asia and beyond. State interventions are reconfigured not simply to reinforce the residual statist tendencies, but to actively construct new comparative advantages and build strong ties with economic elites who can compete in a globalized international economy. Perhaps, more importantly, political elites are forging new social contracts with ordinary citizens to enhance the legitimacy of the state, whether in terms of actively supporting social welfare programmes (as in the case of many conditional cash transfers in Latin America), or by creating new avenues to engage with marginalised groups (for example, through participatory institutions and FPIC process).

Amidst the resource bonanza, development plans were set in motion centred around the exploitation of natural resources. For example, Brazil launched a programme focussed on heavy investments in the capital goods sector, notably in oil, gas and ship-building industries.

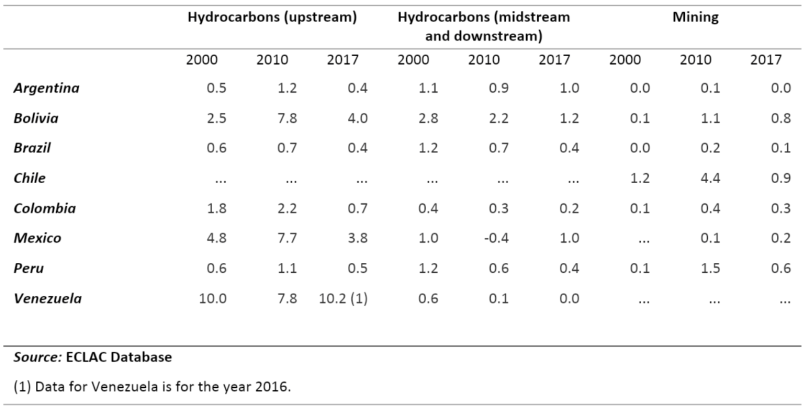

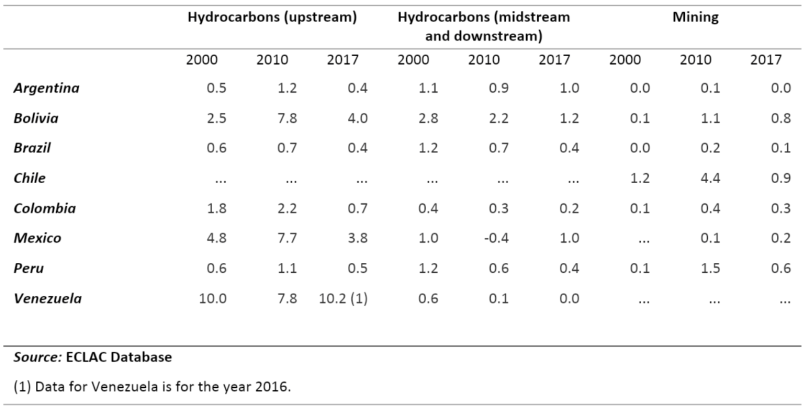

Several Latin American countries also introduced new royalty fees and export taxes aimed at capitalising on high prices. Table 1 details the increasing role of natural resource rents in state revenues over the past twenty years.

Table 1: Public Revenues from non-renewable natural resources in percentages of GDP

Alongside attempts at adding value in mining and hydrocarbons, Latin American governments faced redistributive pressures from their political base. ‘Compensatory states’ justified their resource extraction strategy as a necessary step for further income distribution and revitalization of manufacturing. While political citizenship in post-neoliberal Latin America is increasingly defined by redistributive politics, it also emphasised recognition and identity politics as a central feature of a contentious state-society relationship.

The Limits of the Resource Bonanza

It is now a widely held view that the Left-of-Centre governments successfully reduced poverty and extreme poverty (see Table 2), and although slow, inequality has begun to taper off (Figure 1). However, the data also confirm the fragility of the social achievements of Latin American governments – as the bonanza ended, so did the gains from poverty reduction. This points to several important shortcomings of resource-based strategies.

Figure 1 Gini Inequality Index in Latin America, 2002-2018

Source: CEPAL 2019

Source: CEPAL 2019

Most conspicuously, poverty gains may have created a trade off in making vital investments in the productive economy. Finite domestic revenues have been subject to immense political competition for rent-seeking, and without a coherent industrial strategy, an export-led growth model based on commodities are likely to be fragile and is vulnerable from price swings.

This, then, leads to a gloomy conclusion. Resource-rich states, without the institutional capacity to design a productivist strategy to diversify their export base and to set out an ambitious multi-year development plan to upgrade their industrial sectors, are likely to suffer from the vicissitudes of international commodity markets. At worst, those without political consensus over governance – Venezuela under Maduro being the emblematic case – are likely to waste the opportunities for development through their strategic mining sectors. The broader lesson, I suspect, is that institutional preconditions and pro-industrial policy coalitions are central to the success of developing countries advancing new strategies in an increasingly globalized international economy. Crucially, whenever crisis and uncertainty appear, the state as a stabilizing force becomes more prescient than ever.

Table 2: Poverty and Extreme Poverty in 18 Latin American Countries, 2002-2019 (in percentages)

Jewellord (Jojo) Nem Singh is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of Political Science, Leiden University working on the political economy of development and democracy in Latin America and East Asia. He tweets at @jnemsingh.

The global pandemic and associated developing global recession are calling into question a whole range of economic truths and demanding novel solutions to various interlinked societal problems. In this blog post, I want to connect what we’re currently seeing in the retail sector during this pandemic to deep-seated narratives about the nature of economic exchange, in particular to the notion of “the market”.

The global pandemic and associated developing global recession are calling into question a whole range of economic truths and demanding novel solutions to various interlinked societal problems. In this blog post, I want to connect what we’re currently seeing in the retail sector during this pandemic to deep-seated narratives about the nature of economic exchange, in particular to the notion of “the market”.

The eclipse of neoliberalism in 2000s coincided with the so-called

The eclipse of neoliberalism in 2000s coincided with the so-called

Source:

Source: