By Maria Pia Paganelli and Reinhard Schumacher

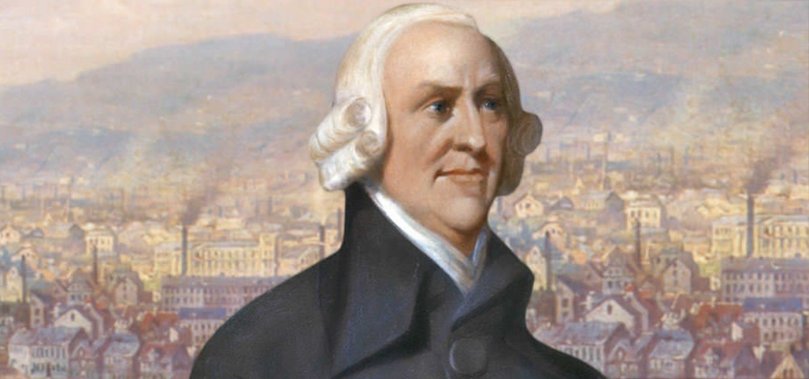

Is trade a promoter of peace? Adam Smith, one of the earliest defenders of trade, worries that commerce may instigate some perverse incentives, encouraging wars. The wealth that commerce generates decreases the relative cost of wars, increases the ability to finance wars through debts, which decreases their perceived cost, and increases the willingness of commercial interests to use wars to extend their markets, increasing the number and prolonging the length of wars. Smith, therefore, cannot assume that trade would yield a peaceful world. While defending and promoting trade, Smith warns us not to take peace for granted. We unpack Smith’s ideas and their relevance for contemporary times in our recent article in the Cambridge Journal of Economics.

Trade as Cooperation or Conflict

Trade can be interpreted as cooperation as well as conflict. The Latin origin of competition is cum- together, and petere- asking, so to come together, to strive together. But in time, it picked up the connotation of fighting against each other. So trade, which is associated with competition, reflects both the creation of bonding among different people and the rivalry, even violent, of some against others.

The idea expanded to the international level. Trade is a “bond of friendship” among nations, but it is also a source of jealousies and conflicts.

Adam Smith illustrates this tension:

“nations have been taught that their interest consisted in beggaring all their neighbours. Each nation has been made to look with an invidious eye upon the prosperity of all the nations with which it trades, and to consider their gain as its own loss. Commerce, which ought naturally to be, among nations, as among individuals, a bond of union and friendship, has become the most fertile source of discord and animosity.” (Wealth of Nations [1776] IV.iii.c.9)

Smith is rightly considered a passionate defender of trade, for both economic and moral reasons. Trade makes everybody better off. Yet, he is also worried that misperceptions and special interests may foment jealousies and conflicts, even to the point of instigating international wars.

How Can Trade Lead to War? The Role of Special Interest Groups and Public Debt

Trade brings wealth, sometimes a lot of wealth. And where there are large profit opportunities, there are powerful interests trying to grab those profits for themselves, or trying to maintain them only for themselves. These special interests are the ones fomenting envy and the false idea that trade is a zero sum game – what I gain is what you lose. It is because their leaders are enriching themselves with trade, that they gain (false) credibility as experts about how to enrich the country. But what they know is how to enrich themselves at the expense of others. They do this with restrictions on trade, subsidies for trade, and demonization of foreign competitors. But what enriches the country is unimpeded trade, not policies that restrict or artificially promote trade.

Nevertheless,

“the mean rapacity, the monopolizing spirit of merchants and manufacturers, who [….] ought not to be the rulers of mankind,” (Wealth of Nations [1776] IV.iii.c.9)

create interest groups so “formidable” that they convince, if not “intimidate,” politicians and the public to follow their (misleading) advice. These special interest groups are willing and able to lead a country to war to establish or protect their trade privileges.

But why do they get so much public support? Wars are destructive and expensive after all.

Adam Smith sees two reasons. First, yes, wars are expensive, but we do not feel it. If wars were paid with taxes, people would feel the burden of wars and would not support them, or at least would not support them for long. But wars are not financed with taxes: they are financed with public debt. Taxes do not increase much, if at all, and the burden is shifted either to the future, or to Neverland, since the size of public debt may grow so large that there is no hope or possibility to pay it down. So the presence of public debt, and its use to finance wars, decreases the perceived cost of war (not the actual cost, which can easily balloon).

Second, wars are not perceived as that destructive for most. Given a professional military, the majority of the people can continue living their life without problems. The conflict zones are far from the home of most citizens, at the fringes of their country or even in foreign countries. As a matter of fact, the majority of the people, feeling no cost and seeing no destruction, see wars as entertainment!

Most people “enjoy, at their ease, the amusement of reading in the newspapers the exploits of their own fleets and armies” and have “a thousand visionary hopes of conquest and national glory” so they are “commonly dissatisfied with the return of peace, which puts an end to their amusement” (Wealth of Nations [1776] V.iii.37)

So, almost 250 years ago, we received a warning: there may be perverse incentives associated with special interests groups capturing political power, and with extensive use of public debt, which can foment envy to the point of bringing about international wars and destroying the benefits and the “bonds of friendship” that trade would otherwise naturally bring.

Maria Pia Paganelli is Associate Professor of Economics at Trinity University, Department of Economics (San Antonio, TX)

Reinhard Schumacher is a postdoc at the Department of Economics and Social Sciences at the University of Potsdam, Germany

[…] Source […]

LikeLike

[…] in opposition to free commerce, and ultimately win the presidency. Suddenly, this largely unheeded warning from Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations sounded extra prescient: “Each nation has been made to […]

LikeLike

[…] turn it against free trade, and eventually win the presidency. Suddenly, this largely unheeded warning from Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations sounded more prescient: “Each nation has been made […]

LikeLike

[…] flip it towards free commerce, and ultimately win the presidency. Abruptly, this largely unheeded warning from Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations sounded extra prescient: “Every nation has been made […]

LikeLike

[…] enduring peace, world peace would have been achieved back in 1776. Ultimately, Smith viewed trade as a potential source of tensions between nations. It has been argued that […]

LikeLike