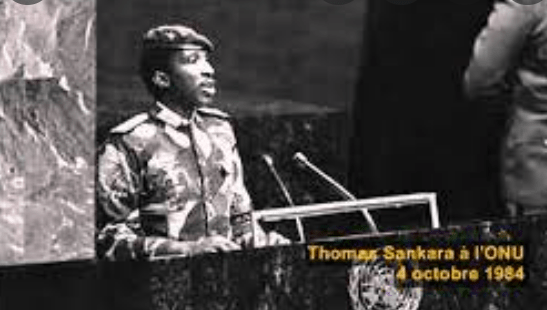

In his speech before the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1984, Thomas Sankara makes the following astute observation regarding the African petite bourgeoisie and its public intellectuals:

“Our professors, engineers and economists are content simply to add a little colouring, because they have brought from the European universities of which they are the products only their diplomas and the surface smoothness of adjectives and superlatives. It is urgently necessary that our qualified personnel and those who work with ideas learn that there is no innocent writing. In these tempestuous times, we cannot leave it to our enemies of the past and of the present to think and to imagine and to create. We also must do so.”

In the same speech, Sankara continues to caution against planning for the uplifting of a nation if such plans are ignorant of, or are wilfully erasing, the disinherited masses and the wretchedness inherited by them. Sankara’s postulation, emerging from the socio-political contexts of the African continent, provides a sound theoretical foundation for knowledge production in the contemporary worlds we inhabit. The popular narratives around climate change have strived to communicate the gravity of planetary collapse and measures required to avert ecological and environmental crises worldwide. Nevertheless, the urgency of envisioning a new world shows little self-reflection as to its epistemic positions and privileges. Climate change discourses in the Global North, academic or otherwise, have largely been constrained by the desire to brave the planetary crises with limited disruption to existing race and class privileges. In terms of how the problems of climate change are identified and defined and the range of solutions to address them, the western epistemologies remain rudimentary.

Consequently, the range of green new deals or the visions for just-transition and sustainable utopias remain agnostic to the everyday realities and struggles of the Global South against imperialism and colonialism. It is unclear if Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour are better placed to partake in these futures than they are now. Max Ajl’s A People’s Green New Deal provides a refreshing and rich scholarly alternative to how an ideal green new deal should be imagined.

A People’s Green New Deal strikes a fine harmony between theory, critique, and discerning avenues towards eco-socialist futures. The book illustrates how the reciprocity between theory and critique could be harnessed to create meaningful conversations around environmental justice and anti-colonialism. The text branches off into two parts. The first part scrutinises the existing green transitions plans and agendas that do not aim for an eco-socialist objective or an endpoint. The second part is more visionary, providing a textured segue into eco-socialism that embodies many possibilities of just futures. The concise core of the book’s argument is – that a people’s green new deal must be based on, amongst others, “universal access to renewable energy, climate debt payments, de-commodified public spaces…and food sovereignty in the (global) South and North…” (p.2). What a People’s Green New Deal hopes to do is not to build another “ecological empire” but to oversee “empire’s end” (p.3). There are no illusions that this will be an easy achievement, especially when it demands the dismantling of imperialist and colonial privileges and institutions.

Max Ajl’s cogent analysis in ‘Capitalist Green Transitions‘ takes no prisoners. The disagreements here emerge from the fact that the power centres, which advance ideas of green transition, have reckoned with neither the nature of climate injustice nor their complicity in perpetuating the planetary collapse that stares us in the face. Further, we must understand what conceptual work terms such as ‘green’ or ‘new deal’ do for us if they fail to interrogate the new frontiers of accumulation conceived within green transition plans or the historical oppression and dispossession of the Global South in myriad forms. The author considers the flimsy escapism of eco-modernist Left (p.42-54), the creation of ‘alternate’ energy futures that are as exploitative as the present (p.57-74), and the docile nature of the Green New Deal pitched by Congressperson Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Ed Markey (p.75-93). Here, the book effectively calls out both the epistemic and teleological problems with the green new deals bandied about in the Global North. Further, the critique extends to the palliative remedies of geoengineering and the tone-deaf enthusiasm of eco-modernism.

The solutions to ongoing environmental catastrophe and injustice cannot be accurate if they have failed to understand the genesis of these problems in colonial plunder, settler colonial erasure, and capital led devastation of more-than-human worlds and Indigenous cosmologies. In his critique, the author repeatedly foregrounds the land and the agrarian question as central to understanding and remedying the problem. Climate change as an issue eludes strict categorisation. Likewise, environmental injustices do not always have a perceptible form. Planetary collapse is an amalgam of dispossession and erasure of Indigenous peoples and their knowledge forms, super-exploitation of the labour, aggravated forms of wealth and income inequality across race, class, and gender, and the relentless extraction of resources from the Global South and the Indigenous lands. We are only staring at multiple reincarnations of ongoing settler colonial projects if the proposed solutions treat climate change as a security threat (p.81), encourage solar geoengineering at the cost of Indigenous sovereignty, or imagine nuclear energy as a panacea for climate instability. The lab-grown climate mitigation, adaptation, or remedial plans of the Green New Deal or eco-modernism are insular from the imperial and colonial realities. The urgency is not so much in recognition of climate catastrophe as much as it is in the forging of a truly revolutionary future when the moment is ripe. Although provocative, the book is a perfect example of why we must understand that decoloniality is not merely an academic exercise but is a vital component of epistemic repositioning in policy, legislative, and juridical spaces, especially in relation to contemporary environmental politics.

In the second part of the book, Max Ajl delivers an exquisite sketch of ideal avenues towards eco-socialism. The text does more than its modest claim – the book may not be a “theoretical treatise on planning for eco-socialist transition” (p.15). However, it invites the readers to expand their political imagination beyond what is known and available. These may include Land-back as a central tenet of climate justice, returning to Indigenous food sovereignty and diverse agroecological practices in the Global South, handing back the stewardship to Traditional Owners for maintaining land, water, and natural resources. ‘A Planet of Fields’, the most vibrant chapter of the book, draws from extensive sources and contemporary examples from Brazil, Cuba, Vietnam, Sumatra etc., to illustrate how endemic knowledge systems and agroecology has been antidotes for industrial agriculture. Ensuring Indigenous food sovereignty would be a primary tool for dismantling corporate agrarian practice and enabling “communities rather than farms…be in control of water, seed, and eventually land” (p.126). While industrial agriculture or livestock production in the Global North has been devastating to the planet and the multispecies world, this is not the only means to carry farming practices elsewhere in the world. The book’s repeated emphasis on looking at evidence from Indigenous practices and traditional agricultural practices in the Global South sets it apart from its predecessors.

The economic and ecological destruction caused by the ‘soybeanization’ of economies in Paraguay and Brazil is neither a simple problem of farming choice or economic policy. It is a complex network of extractive capitalism driving the over-exploitation of labour and land, guided by the consumption choices made elsewhere in the world. On a small scale, Indigenous Paraguayan communities and small farmers have been shifting to sustainable alternatives, such as yarba maté, that address inequalities of land ownership, restore agricultural land eroded by soy and cattle farming, and enable just participation of women in labour. While this may be a small instance of what the book calls “land healing labour” (p.142), our collective vision for the future must have the necessary apparatus to equip and broaden these initiatives. The climate debt, “the formerly colonised world’s rights to reparation, restitution, and development” (p.5), serves the latter function. The string of symptomatic treatments in the form of carbon capture (ineffectual so far) and carbon offsets (literally going up in flames) are already failing miserably as fossil fuel infrastructures continue to flourish. Instead, the resources and the land must be channelled to more meaningful uses, especially towards facilitating resource sovereignty in the Global South.

A People’s Green New Deal is not a mere polemic as a text and as an idea. It is a persuasive endeavour towards what Sankara calls the need to ‘think, imagine, and create’ iterations of justice. The western diagnosis of the climate catastrophe and the tentative remedies have failed at the onto-epistemic front as it excludes the Indigenous voice. Marisol de La Cadena and Mario Blaser call Indigenous cosmologies and knowledge forms’ a world of many worlds’. Planetary collapse is experienced in non-linear, incommensurable ways as it goes about destroying multispecies worlds and amplifies the existing injustices across race, class, and geographies. An environmental revolution from Indigenous perspectives would guarantee a more holistic transformation of both the North and the South in organising and restructuring labour, production, and consumption. In many ways, Max Ajl’s work must be read with the Red Nation’s Red Deal and Bordertown Violence Working Group’s Red Nation Rising as radical futures also entail co-production of knowledge in climate policies. Understanding climate change demands understanding racial and colonial violence.

Moreover, it calls for rethinking about how climate change is not just a problem of global warming or environmental catastrophes but an intricate network of social and economic injustices. In effect, it demands re-learning on our part. The Red Deal and Red Nation tell us about Indigenous peoples’ resistance, resilience, anger, and the centrality of onto-epistemic relations with the land that western knowledge forms have never comprehended. Relearning can be tough, painful, and challenging. However, that is the flesh and blood of solidarity. As Max Ajl suggests for the First World left, “anti-systemic struggles of the periphery” must be “the fundamental departure point for solidarity” (p.93).

The normative idea of green new deals has raised complex questions regarding the politics of expertise in framing alternatives and their implications for the oppressed and marginalised peoples. While the magnitude of climate catastrophes may seem unprecedented to the richer nations, the loss has always been palpable for Indigenous peoples and nations at the periphery in the Global South. If we insist on terming something as unprecedented, it will be attended by a moral question of what we intend to do with that information now. Vanessa de Oliveira Andreotti and others argue that living meaningfully include “…sitting with a system in decline, learning from its history, offering palliative case, seeing oneself in that which is dying, attending to the integrity of the process, dealing with tantrums, incontinence, anger and hopelessness, cleaning up and clearing the space for something new.” The same can be extended to knowledge production and Max Ajl’s A People’s Green New Deal fulfils this mandate flawlessly.

Sakshi is a PhD student at the University of Cambridge, working on Indigenous Environmental Justice in Australia, Brazil, and Canada. Previously, she graduated from the University of Oxford, where she studied for the Bachelor of Civil Law (2014-15), specialising in criminal law and evidence. Her research areas include legal and Indigenous geographies, comparative environmental law, multispecies justice, and political ecology. She tweets at @sakshiaravind.

This book review is a part of a symposium on Max Ajl’s book the People’s Green New Deal. Read the other contributions here.

[…] discussion of this intervention see “A People’s Green New Deal Symposium” including A People’s Green New Deal – An Exercise in Just Knowledge Production, by Aravind Sakshi, Beyond Green Restoration: An Eco-Socialist GND, by Güney Işıkara, and […]

LikeLike