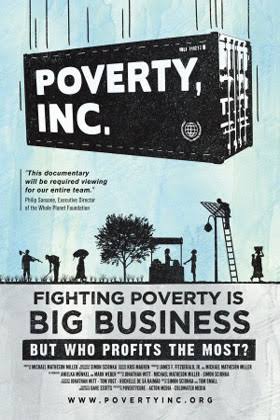

The documentary “Poverty, Inc.” has become so influential that it is now part of many courses at the university level. The good news is that at universities we apply critical thinking to the information we receive (or we are supposed to). As a development economist, I share here my views on this famous documentary.

On the positive side, the documentary does a good job in making some points for an audience unfamiliar with economic theory, such as the idea that dependency does not end poverty, or that current foreign aid (money flows between governments) has “unintended consequences that do more harm than good.” However, both ideas are not new in development studies. The much quoted “teach a human to fish” is an idea associated with many philosophers, including Maimonides (about 850 years ago). This criticism of the structure of current foreign aid is a relatively old idea in the development literature. Perhaps the best point made by the documentary is the argument that Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs) can do a better job if they base their strategies on effective communications with local entities, although this idea is not new either.

What are, then, the problems with this documentary? Many. Firstly, the development literature has two main perspectives; namely, the conservative and the progressive. A documentary that omits a whole branch of argumentation is not responsible and carries “unintended consequences,” such as misinforming that unfamiliar audience. Besides mentioning supranational entities, the documentary did not expose crucial structural problems: there is no serious analysis on geopolitics, global power relations, or class issues, among others. A class analysis would not, for instance, focus on stressing that “NGOs need the poor to exist” but that “the rich need the poor to exist”.

The dominant arguments in the documentary are those from the Austrian school and from “new” institutionalism, both of which argue that the main development problems in poor countries are their poor rule of law and lack of property rights. No mention is made of institutions (in the “old” sense) that can help the poor countries such as global labor standards and a global framework for debt restructuring, among others. In an interview, the co-producer gave the example of China as a case where a freer state has led to development. Did China significantly change its government intervention or strongly protect intellectual property (a sign of good institutions for these schools of thought)? China has benefited from trade (not from free trade), from “reverse engineering” (not from property rights), and from a strong state that heavily intervenes in the market and even blocked some multinational companies that do not adhere to their demands. In fact, in 2017 China ranked worse in property rights than Botswana.

Can the “miracle” of the Asian Tigers (Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea, and Singapore) be attributed to “property rights”? No. Do economies with “strong” institutions have higher entrepreneurship levels than economies with weak institutions? Not exactly. Take the case of Puerto Rico, a colony subject to the“strong” U.S. legal system, where entrepreneurship (approximated by the rate of established business ownership) is weaker than in Peru and Guatemala, countries often criticized for having weak institutions. I agree with the documentary that higher entrepreneurship is needed to develop nations, but the means to create a solid entrepreneurial capacity are far beyond just “property rights.”

Secondly, the documentary mixed foreign aid with all kinds of NGOs to state that NGOs do “more harm than good” because by gifting food or clothes they are harming local producers. Although I agree with the documentary that NGOs are not the development strategy, many NGOs do not gift food and clothes but help to improve the health system and the infrastructure needed to develop a nation. When Food for the Poor constructed houses in a desolated and rural area such as Saltadere (Haiti) for poor families (which put wealth in hands of these families), does that discourage any local producers or “do more harm than good”? No. Actually, local workers learn construction skills on these types of projects. Take the case of the Ethiopian Women Lawyers Association (EWLA), that has won important cases with the funds provided by NGOs. Are these countries better off without the assistance of these NGOs? No.

The documentary failed to recognize that the key question for understanding the difference between good and bad foreign assistance is the same one we must ask in the case of foreign direct investment: does this foreign intervention substitute or complement local capacity? Giving eggs to a rural community that produces eggs substitutes local capacity. An NGO that provides access to vaccines in rural communities complements local efforts to fight against old and curable diseases.

Furthermore, the documentary failed to mention that charity is also necessary for some populations. Few to none can do property rights and global trade to make an old person self-sufficient or to improve the conditions of the sick and the drug addicts that live in the streets, among other population that cannot work.

Thirdly, by generalizing based on anecdotes, the film becomes too simplistic in stating that sending clothes or shoes from abroad harm local producers. Not all countries that receive shoes or clothes are producing them locally and most of the apparel manufactured in poor countries is made by exporting multinationals (e.g., those located in free trade zones in Dominican Republic), therefore, not consumed locally. Does the director know about an academic study showing that in-kind transfers do not harm local purchases? Is the co-producer aware that second-hand clothes are one of the few items that Haitian farmers can sell (to complement their produce sales) to Dominicans in the binational market (a one-day free market that takes place every week in the frontier between these countries)? Middle and high income consumers will continue to consume new clothes from multinationals because of prestige, but if they would buy some used clothes from poor local merchants, that would help development more than buying new clothes from multinationals.

In the case of foreign aid, the film discards it categorically. What we need is to restructure foreign aid. Instead of bringing food from abroad, use that money to buy food locally, enhancing the weak aggregate demand that many battered economies have. One must keep in mind that most of the world income is concentrated in a few Northern countries and is virtually impossible to have a world where all the countries are rich. Without a global government that taxes the rich countries and redistributes to poor countries, some of the existing channels available for redistributing income are: receiving remittances, effectively capturing gains from trade, and attracting foreign transfers, among others. Foreign aid and remittances are not the development solution but if they are well-structured, they can complement local capabilities in poor nations.

Fourthly, by basing their arguments on anecdotes, the documentary enters what economists call the “fallacy of composition”, generalizations based on individual cases. For instance, asking one physician about his living conditions abroad is not representative of all physicians working for NGOs. The film continuously states that there is a “poverty industry”, but we are not sure if this documentary is part of that “industry” because its profits may well exceed those earned by physicians working for $600 per month with Doctors Without Borders in very dangerous places in Syria and Sudan. Such biased analysis does “more harm than good” in ignoring those anonymous heroes that give up a comfortable life in their home countries to work in endangered places.

Another example is when the documentary shows innovators from developing countries without acknowledging that they were among the few privileged residents of these countries that could receive a good education. Innovation requires high quality education, but many rural areas in many poor countries do not even have a free secondary school for the poor. NGOs can complement local efforts in that area by providing scholarships and tutoring, among other efforts.

The film argues through examples that “good jobs are the solution”. No one would disagree. However, the big question remains unaddressed: If not a single country in the world has been able to provide “good jobs” to everyone so as to eradicate poverty, how can a poor economy with limited resources do that for everyone?

I believe that solidarity is better than indifference, and that the ultimate causes of poverty are in the structure of the system, not in the few people that are trying to counteract the system with their available tools. By providing superficial recommendations and pointing fingers at the wrong factors, I believe that this documentary does “more harm than good” because of its “unintended consequences,” such as discouraging good projects in poor countries.

José G. Caraballo is Assistant Professor at the University of Puerto Rico at Cayey.

A slightly different version of this post was published on Huffington Post.

People are poor because they are not allowed to take proper advantage of their opportunities to work. This restriction is due to the way land and other natural resources are owned and rights to them are restricted. Many of the other excuses for poverty have been provided but they lack the basic truth of the above. If the rights to land were better shared and mot monopolized then there would be a gradual reduction in poverty as poor people began to use their abilities to properly earn. Thus poverty is a man-made phenomena due to greed.

LikeLike

Maybe you should concentrate on the massive homeless, drug addicts, and poverty in America before getting involved overseas? How about helping the poor man down the street, or at least getting to know your neighbor?

LikeLike