By Aleksandr V. Gevorkyan and Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven

Over the past decade, the Sub-Saharan African countries’ ability to draw on new debt in international capital markets has become a central characteristic of their development experience. Yet, the determinants of their borrowing costs are driven by external factors where investor perception plays a key role. This raises concerns over the sustainability of the current development model.

In the mid-2000s, 30 African countries received substantial debt reduction through the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank’s Heavily-Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) Initiative. Only a decade later, many of the same countries are again facing debt distress. The African Development Bank recently warned its members of the dangers of rising debt obligations, while the IMF has called for an “urgent need to reset” the region’s growth policies.

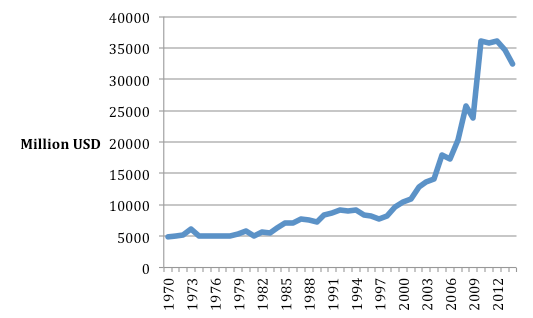

In our new paper entitled “Assessing Recent Determinants of Borrowing Costs in Sub-Saharan Africa” in the November 2016 issue of the Review of Development Economics, we trace the latest round of borrowing back to 2006 with Seychelles as the first sub-Saharan African (SSA) country to issue a sovereign bond, with the exception of South Africa, in 30 years. Since then, DR Congo, Gabon, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, Angola, Nigeria, Tanzania, Namibia, Rwanda, Kenya, Ethiopia and Zambia have all followed suit, accumulating over $25 billion worth of bonds, with a principal amount of more than $35 billion (see Figure 1 for totals by country).Read More »

Morten Jerven, image via Wikimedia

Morten Jerven, image via Wikimedia